We’ve built up a number of simulations over the 7 articles in this series. The last few articles have been looking at linear regression and simulating different intricacies in the data that allow us to explore model assumptions. To end this series, we will now extend the linear model to a mixed model. We will start by building a linear regression model and go through the steps of simulation to build up the hierarchical structure of the data.

For those interesting here are the previous 7 articles in this series:

- Part 1 discussed the basic functions for simulating and sampling data in R

- Part 2 walked us through how to perform bootstrap resampling and then simulate bivariate and multivariate distributions

- Part 3 we worked making group comparisons by simulating thousands of t-tests

- Part 4 building simulations for linear regression

- Part 5 using simulation to investigate the homoskedasticity assumption in regression

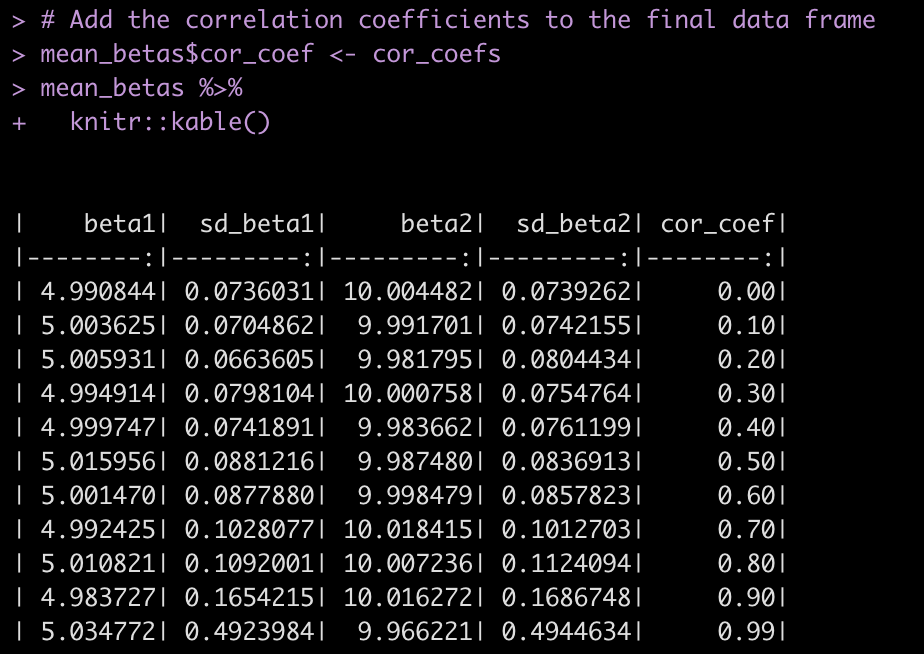

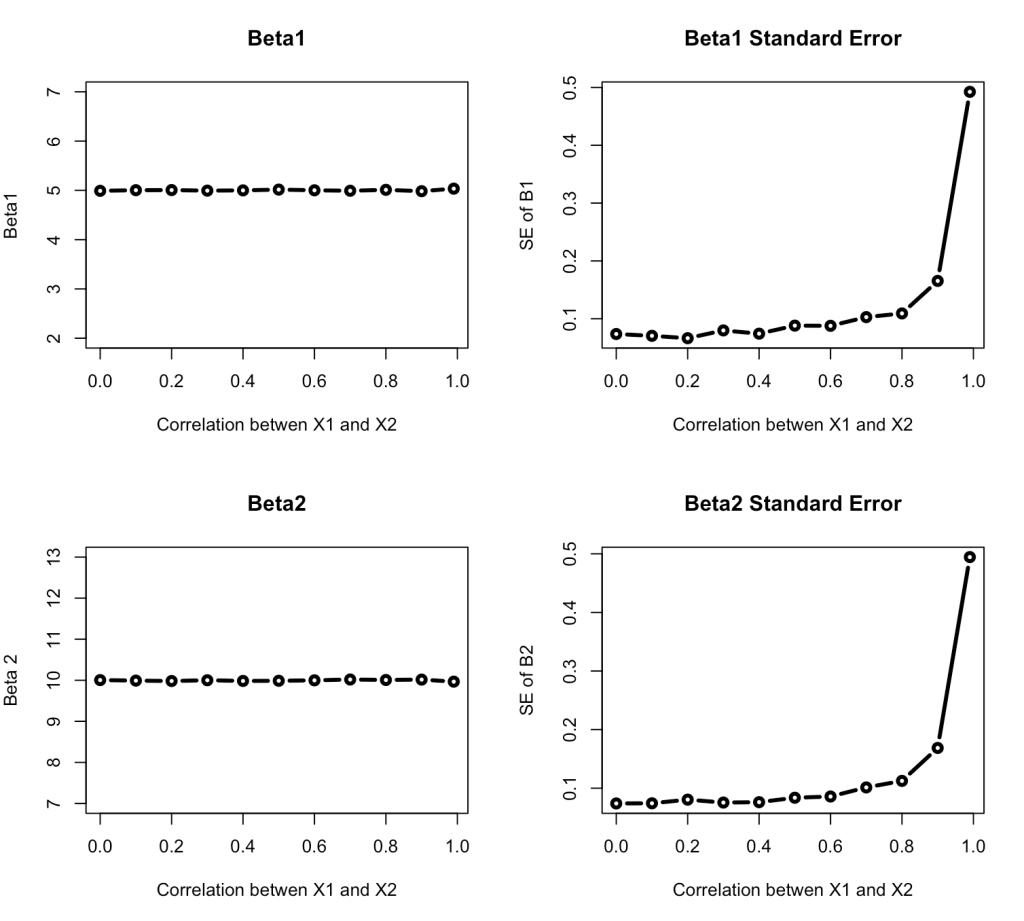

- Part 6 using simulation to investigate the multicollinearity assumption in regression

- Part 7 simulating measurement error in regression

As always, complete code for this article is available on my GitHub page.

Side Note: This is a very code heavy article as the goal is to show not only simulations of data and models but how to extract the model parameters from the list of simulations. As such, this a rather long article with minimal interpretation of the models.

First a linear model

Our data will look at training load for 10 players in two different positions, Forwards (F) and Mids (M). The Forwards will be simulated to have less training load than the Mids and we will add some random error around the difference in these group means. We will simulate this as a linaer model where b0 represents the model intercept and is the mean value for Forwards and b1 represents the coefficient for when the group is Mids.

library(tidyverse)

library(broom)

library(lme4)

theme_set(theme_light())

## Model Parameters

n_positions <- 2

n_players <- 10

b0 <- 80

b1 <- 20

sigma <- 10

## Simulate

set.seed(300)

pos <- rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players)

player_id <- rep(1:10, times = 2)

model_error <- rnorm(n = n_positions*n_players, mean = 0, sd = sigma)

training_load <- b0 + b1 * (pos == "M") + model_error

d <- data.frame(pos, player_id, training_load)

d

Calculate some summary statistics

d %>%

ggplot(aes(x = pos, y = training_load)) +

geom_boxplot()

d %>%

group_by(pos) %>%

summarize(N = n(),

avg = mean(training_load),

sd = sd(training_load)) %>%

mutate(se = sd / sqrt(N)) %>%

knitr::kable()

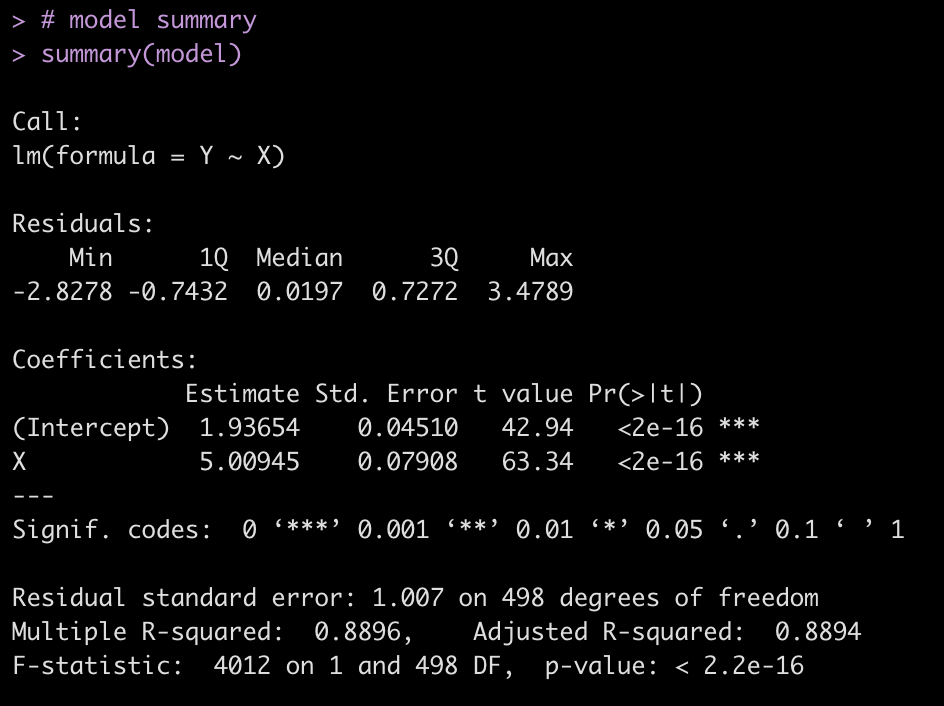

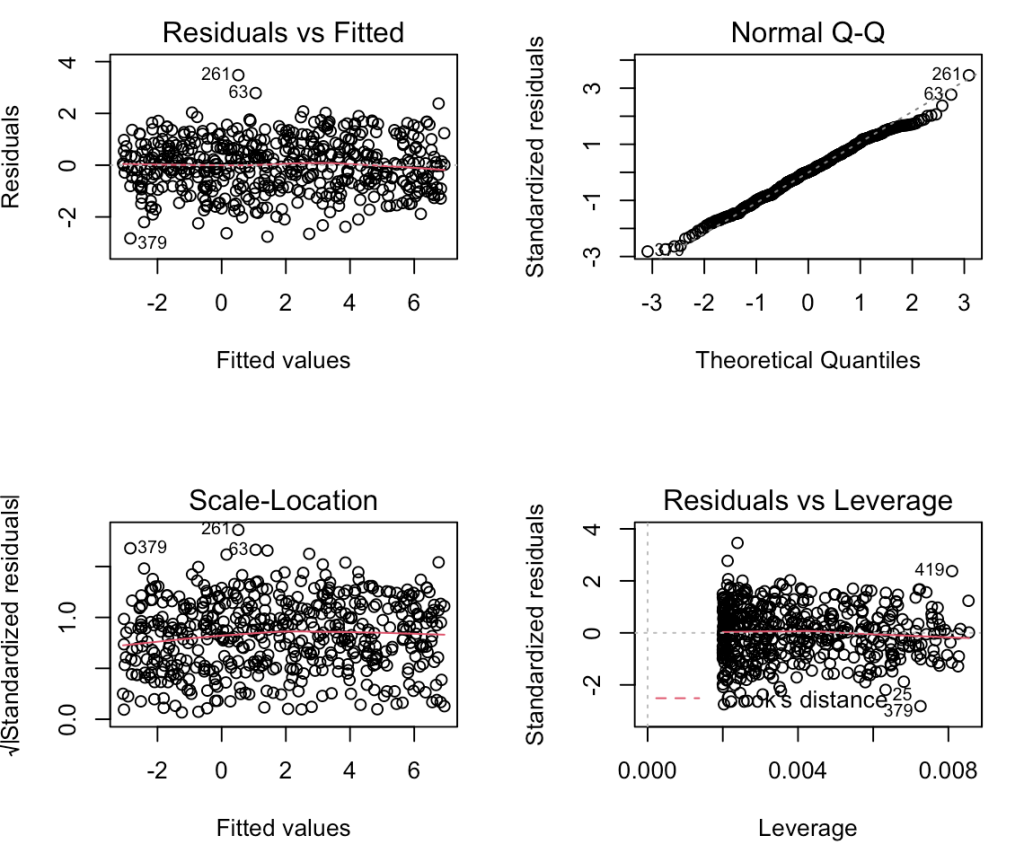

Build a linear model

fit <- lm(training_load ~ pos, data = d) summary(fit)

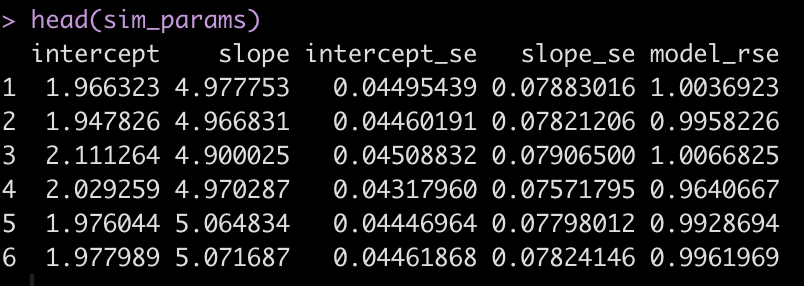

Now, we wrap all the steps in a function so that we can use replicate() to create thousands of simulations or to change parameters of our simulation. The end result of the function is going to be the linear regression model.

sim_func <- function(n_positions = 2, n_players = 10, b0 = 80, b1 = 20, sigma = 10){

## simulate data

pos <- rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players)

player_id <- rep(1:10, times = 2)

model_error <- rnorm(n = n_positions*n_players, mean = 0, sd = sigma)

training_load <- b0 + b1 * (pos == "M") + model_error

## store in data frame

d <- data.frame(pos, player_id, training_load)

## construct linear model

fit <- lm(training_load ~ pos, data = d)

summary(fit)

}

Try the function out with the default parameters

sim_func()

Use replicate() to create many simulations.

Doing this simulation once doesn’t help us. We want to be able to do this thousands of times. All of the articles in this series have used for() loops up until this point. But, if you recall the first article in the series where I laid out several helpful functions for coding simulations, I showed an example of the replicate() function, which will take a function and run it’s result for as many times as you specify. I found this function while I was working through the simulation chapter of Gelman et al’s book, Regression and Other Stories. I think in cases like a mixed model simulation, where you can have many layers and complexities to the data, writing a simple function and then replicating it thousands of times is much easier to debug and much cleaner for others to read than having a bunch of nested for() loops.

Technical Note: We specify the argument simplify = FALSE so that the results are returned in a list format. This makes more sense since the results are the regression summary results and not a data frame.

team_training <- replicate(n = 1000,

sim_func(),

simplify = FALSE)

Coefficient Results

team_training %>%

map_df(tidy) %>%

select(term, estimate) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = estimate, fill = term)) +

geom_density() +

facet_wrap(~term, scales = "free_x")

team_training %>%

map_df(tidy) %>%

select(term, estimate) %>%

group_by(term) %>%

summarize(avg = mean(estimate),

SD = sd(estimate))

Compare the simulated results to the results of the original model fit.

tidy(fit)

Model fit parameters

team_training %>%

map_df(glance) %>%

select(adj.r.squared, sigma) %>%

summarize(across(.cols = everything(),

~mean(.x)))

Compare these results to the original fit

fit %>% glance()

Mixed Model 1

Now that we have the general frame work for building a simulation function and using replicate() we will to build a mixed model simulation.

Above we had a team with two positions groups and individual players nested within those position groups. In this mixed model, we will add a second team so that we can explore hierarchical data.

We will simulate data from 3 teams, each with 2 positions (Forward & Mid). This is a pretty simple mixed model. We will build a more complex one after we get a handle on the code below.

## Model Parameters

n_teams <- 3

n_positions <- 2

n_players <- 10

team1_fwd_avg <- 130

team1_fwd_sd <- 15

team1_mid_avg <- 100

team1_mid_sd <- 5

team2_fwd_avg <- 150

team2_fwd_sd <- 20

team2_mid_avg <- 90

team2_mid_sd <- 10

team3_fwd_avg <- 180

team3_fwd_sd <- 15

team3_mid_avg <- 150

team3_mid_sd <- 15

## Simulated data frame

team <- rep(c("Team1","Team2", "Team3"), each = n_players * n_positions)

pos <- c(rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players), rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players), rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players))

player_id <- as.factor(round(seq(from = 100, to = 300, length = length(team)), 0))

d <- data.frame(team, pos, player_id) d %>%

head()

# simulate training loads

set.seed(555)

training_load <- c(rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team1_mid_avg, sd = team1_mid_sd), rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team1_fwd_avg, sd = team1_fwd_sd), rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team2_mid_avg, sd = team2_mid_sd), rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team2_fwd_avg, sd = team2_fwd_sd), rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team3_mid_avg, sd = team3_mid_sd), rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team3_fwd_avg, sd = team3_fwd_sd)) d ,- d %>%

bind_cols(training_load = training_load)

d %>%

head()

## Average training load by team

d %>%

group_by(team) %>%

summarize(avg = mean(training_load),

SD = sd(training_load))

## Average training load by pos

d %>%

group_by(pos) %>%

summarize(avg = mean(training_load),

SD = sd(training_load))

## Average training load by team & position

d %>%

group_by(team, pos) %>%

summarize(avg = mean(training_load),

SD = sd(training_load)) %>%

arrange(pos)

## Plot

d %>%

ggplot(aes(x = training_load, fill = team)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

facet_wrap(~pos)

Construct the mixed model and evaluate the outputs

## Mixed Model fit_lmer <- lmer(training_load ~ pos + (1 |team), data = d) summary(fit_lmer) coef(fit_lmer) fixef(fit_lmer) ranef(fit_lmer) sigma(fit_lmer) hist(residuals(fit_lmer))

Write a mixed model function

sim_func_lmer <- function(n_teams = 3,

n_positions = 2,

n_players = 10,

team1_fwd_avg = 130,

team1_fwd_sd = 15,

team1_mid_avg = 100,

team1_mid_sd = 5,

team2_fwd_avg = 150,

team2_fwd_sd = 20,

team2_mid_avg = 90,

team2_mid_sd = 10,

team3_fwd_avg = 180,

team3_fwd_sd = 15,

team3_mid_avg = 150,

team3_mid_sd = 15){

## Simulated data frame

team <- rep(c("Team1","Team2", "Team3"), each = n_players * n_positions)

pos <- c(rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players), rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players), rep(c("M", "F"), each = n_players))

player_id <- as.factor(round(seq(from = 100, to = 300, length = length(team)), 0))

d <- data.frame(team, pos, player_id)

# simulate training loads

training_load <- c(rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team1_mid_avg, sd = team1_mid_sd),

rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team1_fwd_avg, sd = team1_fwd_sd),

rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team2_mid_avg, sd = team2_mid_sd),

rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team2_fwd_avg, sd = team2_fwd_sd),

rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team3_mid_avg, sd = team3_mid_sd),

rnorm(n = n_players, mean = team3_fwd_avg, sd = team3_fwd_sd))

## construct the mixed model

fit_lmer <- lmer(training_load ~ pos + (1 |team), data = d)

summary(fit_lmer)

}

Try out the function

sim_func_lmer()

Now use replicate() and create 1000 simulations of the model and look at the first model in the list

team_training_lmer <- replicate(n = 1000,

sim_func_lmer(),

simplify = FALSE)

## look at the first model in the list

team_training_lmer[[1]]$coefficient

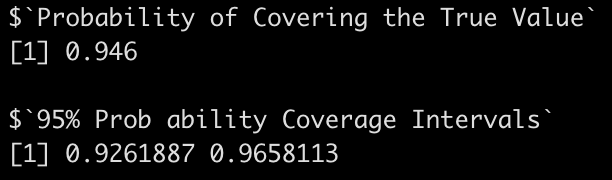

Store the coefficient results of the 1000 simulations in a data frame, create plots of the model coefficients, and compare the results of the simulation to the original mixed model.

lmer_coef <- matrix(NA, ncol = 5, nrow = length(team_training_lmer))

colnames(lmer_coef) <- c("intercept", "intercept_se", "posM", "posM_se", 'model_sigma')

for(i in 1:length(team_training_lmer)){

lmer_coef[i, 1] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[1]

lmer_coef[i, 2] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[3]

lmer_coef[i, 3] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[2]

lmer_coef[i, 4] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[4]

lmer_coef[i, 5] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$sigma

}

lmer_coef <- as.data.frame(lmer_coef) head(lmer_coef) ## Plot the coefficient for position lmer_coef %>%

ggplot(aes(x = posM)) +

geom_density(fill = "palegreen")

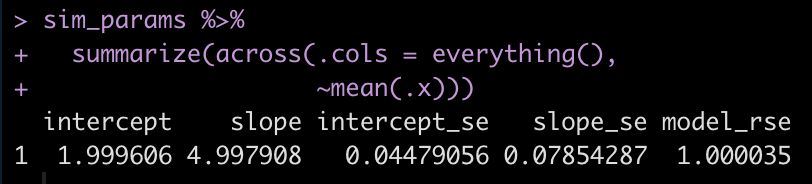

## Summarize the coefficients and their standard errors for the simulations

lmer_coef %>%

summarize(across(.cols = everything(),

~mean(.x)))

## compare to the original model

broom.mixed::tidy(fit_lmer)

sigma(fit_lmer)

Extract the random effects for the intercept and the residual for each of the simulated models

ranef_sim <- matrix(NA, ncol = 2, nrow = length(team_training_lmer))

colnames(ranef_sim) <- c("intercept_sd", "residual_sd")

for(i in 1:length(team_training_lmer)){

ranef_sim[i, 1] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$varcor %>% as.data.frame() %>% select(sdcor) %>% slice(1) %>% pull(sdcor)

ranef_sim[i, 2] <- team_training_lmer[[i]]$varcor %>% as.data.frame() %>% select(sdcor) %>% slice(2) %>% pull(sdcor)

}

ranef_sim <- as.data.frame(ranef_sim) head(ranef_sim) ## Summarize the results ranef_sim %>%

summarize(across(.cols = everything(),

~mean(.x)))

## Compare with the original model

VarCorr(fit_lmer)

Mixed Model 2

Above was a pretty simple model, just to get our feet wet. Let’s create a more complicated model. Usually in sport and exercise science we have repeated measures of individuals. Often, researchers will set the individual players as random effects with the fixed effects being the component that the researcher is attempting to make an inference about.

In this example, we will set up a team of 12 players with three positions (4 players per position): Forward, Mid, Defender. The aim is to explore the training load differences between position groups while accounting for repeated observations of individuals (in this case, each player will have 20 training sessions). Similar to our first regression model, we will build a data frame of everything we need and then calculate the outcome variable (training load) with a regression model using parameters that we specify. To make this work, we will need to specific an intercept and slope for the position group and an intercept and slope for the individual players as well as a model sigma value. Once we’ve done that, we will fit a mixed model, write a function, and then create 1000 simulations.

## Set up the data frame

n_pos <- 3

n_players <- 12

n_obs <- 20

players <- as.factor(round(seq(from = 100, to = 300, length = n_players), 0))

dat <- data.frame( player_id = rep(players, each = n_obs), pos = rep(c("Fwd", "Mid", "Def"), each = n_players/n_pos * n_obs), training_day = rep(1:n_obs, times = n_players) ) dat %>%

head()

## Create model parameters

# NOTE: Defender will be the intercept

set.seed(6687)

pos_intercept <- 150

posF_coef <- 170

posM_coef <- -70

individual_intercept <- 50

individual_slope <- 10

sigma <- 10

model_error <- rnorm(n = nrow(dat), mean = 0, sd = sigma)

## we will also create some individual player variance

individual_player_variance <- c()

for(i in players){

individual_player_variance[i] <- rnorm(n = 1,

mean = runif(min = 2, max = 10, n = 1),

sd = runif(min = 2, max = 5, n = 1))

}

individual_player_variance <- rep(individual_player_variance, each = n_obs)

dat$training_load <- pos_intercept + posF_coef * (dat$pos == "Fwd") + posM_coef * (dat$pos == "Mid") + individual_intercept + individual_slope * individual_player_variance + model_error dat %>%

head()

## Average training load by pos

dat %>%

group_by(pos) %>%

summarize(avg = mean(training_load),

SD = sd(training_load))

## Plot

dat %>%

ggplot(aes(x = training_load, fill = pos)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5)

Construct the mixed model and evaluate the output

## Mixed Model fit_lmer_pos <- lmer(training_load ~ pos + (1 | player_id), data = dat) summary(fit_lmer_pos) coef(fit_lmer_pos) fixef(fit_lmer_pos) ranef(fit_lmer_pos) sigma(fit_lmer_pos) hist(residuals(fit_lmer_pos))

Create a function for the simulation

sim_func_lmer2 <- function(n_pos = 3,

n_players = 12,

n_obs = 20,

pos_intercept = 150,

posF_coef = 170,

posM_coef = -70,

individual_intercept = 50,

individual_slope = 10,

sigma = 10){

players <- as.factor(round(seq(from = 100, to = 300, length = n_players), 0))

dat <- data.frame(

player_id = rep(players, each = n_obs),

pos = rep(c("Fwd", "Mid", "Def"), each = n_players/n_pos * n_obs),

training_day = rep(1:n_obs, times = n_players)

)

model_error <- rnorm(n = nrow(dat), mean = 0, sd = sigma)

individual_player_variance <- c()

for(i in players){

individual_player_variance[i] <- rnorm(n = 1,

mean = runif(min = 2, max = 10, n = 1),

sd = runif(min = 2, max = 5, n = 1))

}

individual_player_variance <- rep(individual_player_variance, each = n_obs)

dat$training_load <- pos_intercept + posF_coef * (dat$pos == "Fwd") + posM_coef * (dat$pos == "Mid") + individual_intercept + individual_slope * individual_player_variance + model_error

fit_lmer_pos <- lmer(training_load ~ pos + (1 | player_id), data = dat)

summary(fit_lmer_pos)

}

Now use `replicate()` and create 1000 simulations of the model and look at the first model in the list.

player_training_lmer <- replicate(n = 1000,

sim_func_lmer2(),

simplify = FALSE)

## look at the first model in the list

player_training_lmer[[1]]$coefficient

Store the coefficient results from the simulations, summarize them, and compare them to the original mixed model.

lmer_player_coef <- matrix(NA, ncol = 7, nrow = length(player_training_lmer))

colnames(lmer_player_coef) <- c("intercept", "intercept_se","posFwd", "posFwd_se", "posMid", "posMid_se", 'model_sigma')

for(i in 1:length(player_training_lmer)){

lmer_player_coef[i, 1] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[1]

lmer_player_coef[i, 2] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[4]

lmer_player_coef[i, 3] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[2]

lmer_player_coef[i, 4] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[5]

lmer_player_coef[i, 5] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[3]

lmer_player_coef[i, 6] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$coefficients[6]

lmer_player_coef[i, 7] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$sigma

}

lmer_player_coef <- as.data.frame(lmer_player_coef) head(lmer_player_coef) ## Plot the coefficient for position lmer_player_coef %>%

ggplot(aes(x = posFwd)) +

geom_density(fill = "palegreen")

lmer_player_coef %>%

ggplot(aes(x = posMid)) +

geom_density(fill = "palegreen")

## Summarize the coefficients and their standard errors for the simulations

lmer_player_coef %>%

summarize(across(.cols = everything(),

~mean(.x)))

## compare to the original model

broom.mixed::tidy(fit_lmer_pos)

sigma(fit_lmer_pos)

Extract the random effects for the intercept and the residual for each of the simulated models.

ranef_sim_player <- matrix(NA, ncol = 2, nrow = length(player_training_lmer))

colnames(ranef_sim_player) <- c("player_sd", "residual_sd")

for(i in 1:length(player_training_lmer)){

ranef_sim_player[i, 1] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$varcor %>% as.data.frame() %>% select(sdcor) %>% slice(1) %>% pull(sdcor)

ranef_sim_player[i, 2] <- player_training_lmer[[i]]$varcor %>% as.data.frame() %>% select(sdcor) %>% slice(2) %>% pull(sdcor)

}

ranef_sim_player <- as.data.frame(ranef_sim_player) head(ranef_sim_player) ## Summarize the results ranef_sim_player %>%

summarize(across(.cols = everything(),

~mean(.x)))

## Compare with the original model

VarCorr(fit_lmer_pos)

Wrapping Up

Mixed models can get really complicated and have a lot of layers to them. For example, we could make this a multivariable model with independent variables that have some level of correlation with each other. We could also add some level of autocorrelation for each player’s observations. There are also a number of different ways that you can construct these types of simulations. The two approaches used here are just dipping their toes in. Perhaps in future articles I’ll put together code for more complex mixed models.

All of the code for this article and the other 7 articles in this series are available on my GitHub page.